Photo Report: A Visit To The Ultimate Vintage Patek Philippe Vault

Documenting the many chapters of Patek Philippe at Collectability

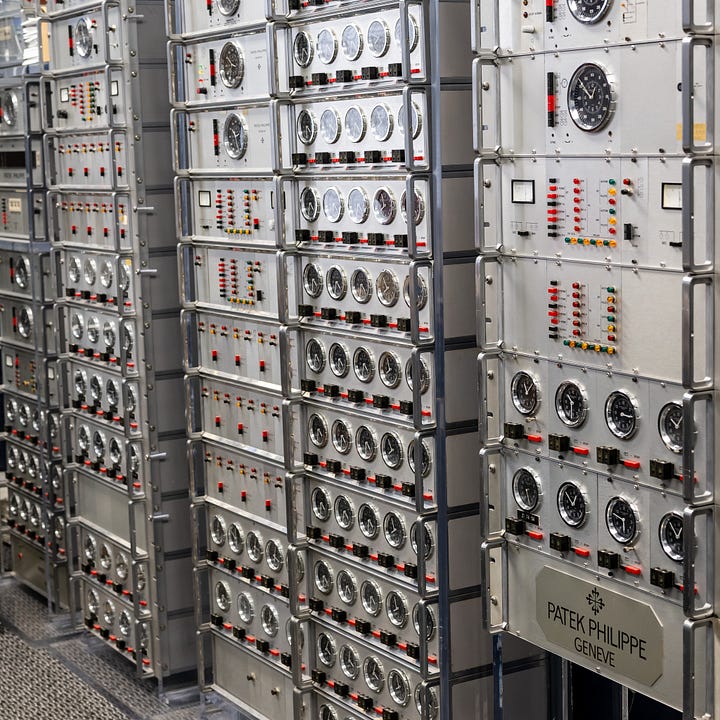

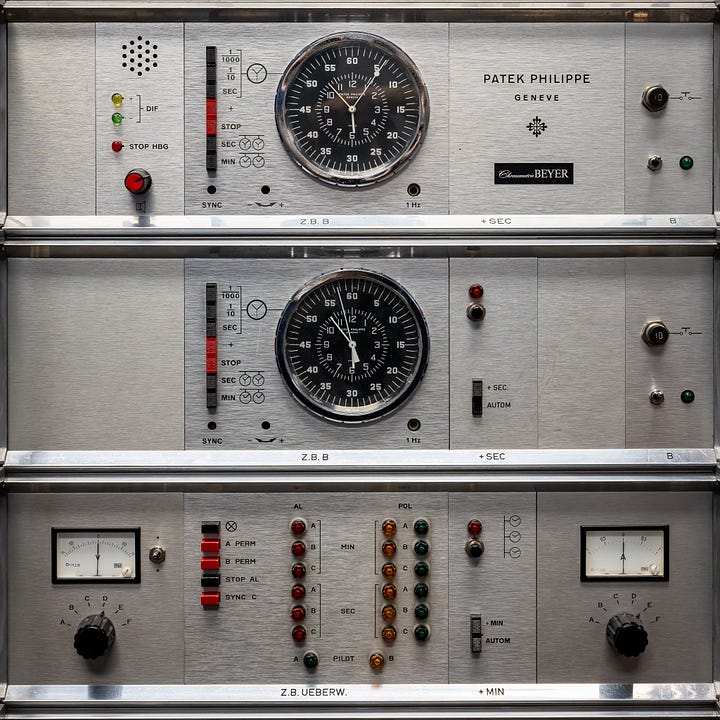

Patek Philippe established its Electronic Timekeeping Division in 1948. Over the next few decades, it perfected electronic technology, creating some of the most cutting-edge and precise master clocks for the Vatican, NASA, the UN, and airports and railways around the world. Rolex even used Patek Philippe’s timing systems in its manufacturing facilities.

Today, the largest collection of electronic Patek Philippe clocks sits in a nondescript office building outside New York City. It’s the headquarters of Collectability, the dealer founded by John Reardon and co-founder Tania Edwards dedicated to all things Patek Philippe.1

I’m writing a series of collector’s guides for Collectability (3970 was first), so visited them during a recent trip to NYC.

Collectability is one of the few places where you can grasp the full breadth of Patek Philippe.2 It’s not just wristwatches. It’s an entire world of timekeeping spanning nearly 200 years.

There’s a clock, book, or other Patek paraphernalia everywhere you look.

These artifacts are a reminder that until a couple of generations ago, knowing the time—and I mean the exact time—was hardly a given. The companies that could tell the time ruled the world. Until recently, these weren’t just mechanical watch companies. These were technology companies, tasked with keeping the world on time.

Somewhere along the way, that changed. The transistor was invented in 1947, and everything started getting smaller.

A new breed of technology company was born, and before long, they started making mini wrist computers that happened to tell time. Casio and Texas Instruments gave way to Apple and Google.

In the meantime, Patek Philippe and its watchmaking brethren started looking backwards instead of forwards. They became purveyors of a certain old-world luxury, trading on heritage, craft, and nostalgia.

It’s beautiful and maddening, as we demand they simultaneously innovate and respect their own history.

Those big electronic clocks sit as a final marker of an era when watch and clockmakers ran the world, or at least kept it running on time.

Flick of the wrist

While the electronic clocks are a curious chapter of Patek Philippe’s history, the mid-20th century was mostly the golden age of wristwatches.

I spent most of my time looking at vintage watches, but there were also plenty of modern Pateks. Some make it to Collectability’s website, but many don’t. Visiting a dealer is a reminder that their public-facing presence is only the tip of the iceberg.

Here are a few favorites.

This pair of Calatravas has a lot in common: large gold case, unusual lugs, silver dial with Roman numerals, and rare. Less than 10 examples of the 1589 are known in rose gold, and only four 1596s are known. These uncommon references were probably overshadowed by better-known Calatravas—refs. 565, 570, 2508—but illustrate the breadth of ideas from Patek Philippe at the time.

During the last few years when everyone seemed to want a modern Nautilus, Thierry Stern said he “[didn’t] want steel taking over the lead in the whole collection.” The sheer variety of vintage watches on display at Collectability reminded me what an anomaly these years have been. In this Photo Report, there’s exactly one stainless steel watch (the ref. 130 chronograph, below) and no Nautilus. Patek Philippe has had many collections and chapters, some more enduring than others.

Shaped watches are an important chapter in Patek Philippe’s history. One of Collectability’s favorites is the Ellipse. John and Tania’s love for it is infectious, and this ref. 3738 is the watch I most wanted to take home. Patek Philippe launched the Ellipse (refs. 3546 and 3548) in 1968; it was popular and quickly grew to other wristwatches, but also rings, lighters, and other accessories.

The ref. 3586 “Golden Circle,” feels like the cousin of the Ellipse. Produced from 1970-80, it uses Patek’s caliber 350, an unusual back-winding movement.

Patek launched the “Nautellipse” ref. 3770 in 1980. It’s a time when the hot watch was the Ellipse. Meanwhile, the Nautilus was selling, but not super well–it was too big and expensive. Patek wanted a sporty, waterproof Ellipse, and the Nautellipse was born. Patek even used the same casemaker (Favre & Perret) for the ref. 3770 as it did for the Nautilus.

“For a quartz watch, it’s still quite mechanical,” Collectability’s watchmaker said when taking apart these Beta 21s. After watching him take apart a few different watches, the process felt completely analytical and objective, whether the watch is quartz or mechanical, $10k or $100k.

As much as any complication, I associate Patek Philippe with the travel time.3 It began with this ref. 2597 HS (for Heures Sautantes, or Jumping Hours), the first series seen here was only produced from 1958 to 1961. The buttons on the side simply jump the hour back or forward. The second series came soon after and added an additional hour hand for tracking another time zone. At the time, Patek Philippe offered a kit to upgrade the first series watches, which means few 2597s exist today without the additional hand.

Patek made only about 280 steel 130 chronographs in the 1930s and ‘40s. At 33mm, it was the perfect sports watch then and now.

Probably my favorite Calatrava, and even better in rose gold. Introduced in 1950, the Patek Philippe 2508 features a larger (35mm), waterproof case from Taubert/Borgel. They're best with this dial design, featuring geometric markers that would make Euclid proud.

I don’t have much more to say about the 3970 perpetual calendar chronograph. It was a treat to see a second series 3970R and a 3970/002J together. The bracelets aren’t exactly my style, but Patek can make a damn good one.

For more, visit Collectability.

The Roundup

🌝 A special Patek Philippe 96 calendar coming soon. Sotheby’s Sam Hines posted a unique complete calendar ref. 96 with Breguet numerals that will be at Sotheby’s April Hong Kong auction. There are only 8 known complete calendar moonphase ref. 96s (“The Last Emperor’s” sold for 5m+ in 2023). When Phillips sold the Last Emperor’s 96, I documented all of them—this one last sold at Christie’s in 2011 for CHF 500k. For me, this 96 will be one of the highlights of the spring auctions.

🏪 Watchfinder to open its first boutique in the U.S. Watchfinder, the online-first preowned dealer Richemont acquired for a reported £250m in 2018, continues to expand its physical footprint. It has a job listing for a boutique manager role in Soho, New York. I think it’d be Watchfinder’s first real boutique in the States–it currently has one location listed on its website, which is really just Richemont’s U.S. office.

🚗 Why don’t more watch brands do this? BMW put its entire historical catalog online for anyone to browse with full historical info, images, production numbers, even spare parts. I’ve mentioned Audemars Piguet’s excellent efforts to document its history with AP Chronicles over the last few years, but it seems like more brands should be doing this.

With any luck, I’ll publish two more newsletters by Monday: A Watches & Wonders preview and an interview with Parmigiani Fleurier CEO Guido Terreni. Stay tuned!

Get in touch:

tony[at]unpolishedwatches.com (please use this email, replies to the newsletter often get lost).

❣️ Please, please tap the heart or leave a comment if you like this issue—it helps me understand the type of content you enjoy:

In Case You Missed It:

It’s worth reading Collectability’s full history on Patek Philippe’s electronic clocks.

Along with the Patek Philippe Museum.

Okay, after the perpetual calendar chrono.

Is there any info on that giant bank of electronic master clocks? They make up the background of John Reardon’s videos and I’ve always been intrigued. Where did they come from? What were they used for? Does John own them? Are they for sale? I’d love a dedicated article on them!

MrT, again the highlight of the weak (hearing from you). Seeing that rose 1589 on the Collectability site, I thought of my YG 1516 which is slightly earlier (around 1942-48) which too has the 'welded lugs' and applied indexes to the dial (complete I-XII). Only issue is my guy is 32mm and was found locally here in South Africa (think any PP as rarer than rocking horse 💩). Power to your pencil...